Re Doordash & TWU landmark agreement implications to “gig” workers

Listen to the full Podcast or Susan’s Interview @ 1:39:50 to 1:46

Re Doordash & TWU landmark agreement implications to “gig” workers

Listen to the full Podcast or Susan’s Interview @ 1:39:50 to 1:46

Here at Susan Moriarty & Associates, we are always evolving and adapting for our clients and guests of the office.

We have now introduced the Check-in QLD QR Code so that any person attending the office can sign in conveniently. The QR Code is displayed at the front of the office on our receptionist’s desk. For those attending the office that do not have the app, we still have our COVID-19 sign-in book available to fill out. The book sits atop the reception desk, for your convenience.

We ask that if you do attend the office, please ensure you are correctly socially distancing by maintaining 1.5metres between yourself and the staff and that you wear your mask during any meetings or consultations with the solicitors.

Thank you for your understanding.

Law firms are classified under the Queensland Government legislation as an essential service. So here at SMA, our solicitors are still working through the COVID-19 outbreak and any subsequent lockdowns. Our office is open during regular business hours and appointments are able to be scheduled by Zoom, Microsoft Teams, or via telephone.

To book now, call us on 07 3352 6782 or email us at admin@susanmoriarty.com.au

One of Australia’s top businessmen has quit Sydney’s exclusive men’s only club, after it voted to keep women out. The institution, located in the heart of Sydney CBD, voted down a resolution which would have altered the club’s rule prohibiting women from joining.

As a human rights lawyer, Susan Moriarty was interviewed by the ABC to weigh in on the controversial debate regarding one of the state of New South Wales’s iconic institutions.

Linked below is the interview between the ABC and our Principal, Susan Moriarty.

Listen here to ABC News Radio! Posted Tuesday 16 June 2021.

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer before you rely on this information.

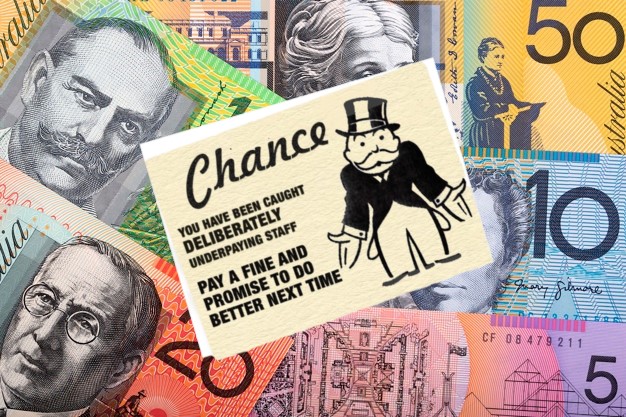

With Australia’s economy plunging into its first recession in almost 30 years, it’s no surprise many employers are looking for ways to cut costs.

But what happens when this cost-cutting clashes with your workplace rights?

Linked below is a helpful article by the ABC News which answers this very question.

Can your boss cut your pay or conditions without asking you? How does coronavirus affect workplace rights? by Business Reporter Michael Janda posted Tuesday 1 September 2020.

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer before you rely on this information.

Susan Moriarty & Associates acts for Ms Liesa Oldfield, former Human Resources Manager of One Stop Warehouse Limited (‘OSW’) – Australia’s largest solar panel distributor. The solar giant, founded by chief executive, Anson Zhang, and co-founder Jeffrey Yu, is a national company with offices in all state capitals. In 2019, OSW was one of Australia’s fastest-growing private companies. Relevantly, in September of 2019, The Australian Financial Review reported that “Zhang’s One Stop Warehouse Group grew revenue 108 per cent to $391 million in 2018-19, the most of any company on the Top 500 Private Companies List”. 37-year-old Chinese-born Queenslander, Mr Zhang, was on the 2019 Financial Review Young Rich List and won a 2019 Australian Young Entrepreneur Manufacturing, Wholesale & Distribution Award, together with Yu.

In October 2019, Ms Oldfield filed a general protections application against OSW, Zhang and Wu alleging unlawful adverse action during her employment from 3 April 2017 to 2 November 2018. Ms Oldfield claims that in contravention of s.340 of the Fair Work Act 2009 (‘FW Act’) adverse action was taken against her because she had, or had exercised workplace rights as defined by s.341 of the FW Act. She also claims that adverse action was taken against her because of her race, national extraction or social origin and an imputed disability contrary to s.351 of the FW Act. The adverse action she pleads as having been taken against her is:

(a) injuring her in her employment or altering her position to her prejudice by:

(i) removing the payroll process from her position;

(ii) countermanding a verbal warning issued by her to an employee;

(iii) employing a HR assistant;

(iv) removing Warehouse recruitment from her roll;

(v) removing her WHS role;

(vi) advising her she did not fit the “culture” of the business;

(vii) suggesting she was “unstable”;

(viii) advising her a number of complaints had been made against her;

(ix) removing her from sales team recruitment duties;

(x) progressively removing her core duties and responsibilities;

(b) discriminating between her and other employees by:

(i) removing payroll process responsibility;

(ii) removing Warehouse staff recruitment from her role;

(iii) injuring her by causing her humiliation anxiety and distress; and

(c) injuring her in her employment by exposing her to liability as an involved person pursuant to s.550 of the Act to civil penalties for contraventions of the Act as a result of failure to rectify contraventions brought to the respondents’ attention by her in her roles as HR Officer and HR Manager.

On 8 July 2020, Judge Jarrett of the Federal Circuit Court in Brisbane delivered an interlocutory judgment, (Oldfield v One Stop Warehouse Pty Ltd & Ors [2020] FCCA 1865) dismissing the Respondents application to strike out Ms Oldfield’s claim on jurisdictional grounds stating that Ms Oldfield “claims to have been put in the invidious position that she was responsible for human resources at a company which did not comply with its legal obligations towards its workforce. She alleges that she made various complaints and sought, to no avail, an indemnity from her employer in the event of an investigation by the Fair Work Ombudsman of the business.”

The Respondents sought to strike out Ms Oldfield’s substantive application and claim on an interesting point regarding the jurisdictional parameters for a person filing a General Protections Claim involving Dismissal (pursuant to section 365 of the FW Act) and the Courts ability to deal with such dispute (pursuant to section 370 of the FW Act) and a person filing a General Protections Claim Not Involving Dismissal (pursuant to section 372 of the FW Act). Importantly, as Judge Jarrett, detailed at [11]:

…if a person has resigned from his or her employment, but was forced to do so because of conduct, or a course of conduct, engaged in by her employer, then that employee has been dismissed for the purposes of the Fair Work Act. If they allege that they were dismissed in contravention of Part 3–1 of the Act, they cannot bring a general protections court application in relation to the dispute unless they meet the conditions set out in s.370(a) or (b) of the Act.

Whilst Ms Oldfield resigned from her employment to avoid exposure to liability for any Fair Work Ombudsman investigation regarding One Stop Warehouse underpaying its employees, she does not claim that her resignation was a constructive dismissal or that it was adverse action taken against her by the first respondent.

After a consideration of the issues and the legislation, Judge Jarrett ultimately dismissed the Respondents’ application for summary dismissal of Ms Oldfield’s claim finding that:

19. The applicant does not allege she was dismissed in contravention of Part 3-1 of the Act. Whilst the circumstances of her resignation might mean that she was dismissed according to the definition in s.385 of the Act as the respondents argue, her case is not that she was dismissed in breach of a general protection.

20. Because she does not argue that she was dismissed in contravention of Part 3-1 of the Act she is not a person caught by s.370 of the Act. She is not a person who was entitled to apply under s.365 for the Commission to deal with her dispute. That is because she does not allege, and seemingly has never alleged, that she was dismissed in contravention of Part 3–1 of the Act. Whilst she does claim that the first respondent took adverse action against her, the adverse action that she alleges the first respondent took for one or more proscribed reasons does not include her dismissal, actual or constructive. Nothing in the previous proceedings taken by her in the Fair Work Commission indicates to the contrary. In those proceedings, she may have claimed that she was forced to resign but I do not understand that her case was that she was forced to resign because of the adverse action that was taken against her. In any event, that is not her case in these proceedings.

21. The applicant’s application is not liable to be summarily dismissed on the basis that her claims for relief are frivolous, vexatious or an abuse of the process of the Court. I cannot be satisfied that her claim generally has no reasonable prospects of success. She pleads material facts that, if accepted, may lead to the grant of the relief or part of it, that she claims. The basis of the respondents’ claims to have the proceedings dismissed is not made out. The applicant’s claim is not a dismissal dispute for the purposes of the Fair Work Act and she is not precluded from bringing these proceedings by s.370 of that Act.

With regards to the Respondents’ alternative claim of relief to strike out parts of Ms Oldfield’s claim that if the applicant was not dismissed because her resignation was voluntary, then the Respondents cannot be liable to compensate the applicant for the consequences of her own decision, Judge Jarrett ultimately refused the relief sought and found that:

30. Whilst the applicant does not accept that she has no reasonable prospects of success on this aspect of her claim, she does concede that at trial it may be more difficult to persuade the Court that it is appropriate to make an order for compensation in respect of her claimed economic loss.

31. She argues that her economic loss is a loss which may be characterised as “a not unlikely consequence of the taking of the adverse actions against the applicant”. Thus, she argues, the loss incurred after the applicant’s decision to resign her employment may therefore be argued to be loss which has a sufficient causal connection with the contraventions of the Act to be compensable. She argues that the Court may be persuaded to exercise the discretionary power to order that the respondents pay compensation in respect of part or all of that loss and that is properly a matter to be considered in the light of all the evidence at trial.

32. I accept that argument. The question of causation – that is to say what compensation is due to the applicant because of the adverse action taken against her – may be answered by an examination of the reasonableness of the applicant’s decision to resign her employment. It is not difficult to envisage that confronted with the situation as described by the applicant in her pleading, it would be a reasonable thing for her to resign her employment so as to limit her exposure to any accessorial liability. Her resignation might be seen as a reasonable and foreseeable consequence of the adverse action taken against her.

33. I cannot accept the respondents’ argument that merely because the applicant chose to resign her employment, she has no reasonable prospect of successfully pursuing a claim for economic loss. Given that the basis upon which the respondents seek to have this aspect of the applicant’s claim “struck out” is that she has no reasonable prospect of successfully pursuing this aspect of her claim, their application for relief must be refused.

On 16 July 2020, the Respondents’ filed an application to appeal Judge Jarrett’s decision to the Federal Court of Australia. On 17 July 2020, the parties attended mediation before a Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia, but the matter failed to resolve. The matter is back on for directions before Judge Jarrett on 21 August 2020.

Benedict Coyne, Special Counsel at SMA who has carriage of Ms Oldfield’s matter stated:

“We are delighted that the Court has so clearly said that our client has a right to be heard on her claims but incredibly disappointed that One Stop Warehouse has now filed an appeal against this Decision.

Now that mediation has failed, this will add further delay to our client telling the Court of the incidents she has documented in her pleadings and affidavit.

Nevertheless, she is committed to telling the truth to the Court so that her colleagues, who may not be able to do so, receive their rightful wage and benefit entitlements as soon as possible.”

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer before you rely on this information.

As Queensland’s COVID-19 curve reduces and restrictions ease, plans for returning to work are a hot topic among many businesses.

But before rushing back to business as usual, the Government is urging workplaces to implement a plan outlining how they will keep returning workers safe in accordance with their key workplace health and safety (‘WHS’) duties.

Importantly, employers owe their employees a duty to provide and maintain a working environment that is safe and without risk.

Under this duty falls the responsibility to protect employees from exposure to COVID-19.

Numerous health and safety recommendations have been released regarding what action employers should be taking to prevent exposing their employees to COVID-19 and other related risks upon returning to work.

For more consumable reading, we have condensed some of the important suggestions into one easy-to-read factsheet.

With workplaces adapting to reflect community changes such as caring responsibilities and commuting needs, employers are tasked with creating an environment which is enjoyable and safe for their workers.

Certainly, not all employees will feel the same about returning to work, because no two workers or workplaces are the same. You will need to understand what is right for each individual to format a return to work plan.

Importantly, Australian HR Institute suggests that support & communication is paramount – urging employers to prioritise their workers’ emotional safety.

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer before you rely on this information.

Our guest contributor, Dr Anchita Karmaker, brings a wealth of skill and knowledge bridging the great divide between legal and medical professions. Having worked for 11 years as a medical practitoner in Australia, she is currently completing her legal qualifications, with the hope to specialise in regulatory and administrative/constitutional legal issues at Susan Moriarty & Associates.

Once you finish all those years of grueling study with sleepless nights, finally you get to call yourself a healthcare professional. Whether you are a Doctor, a Dentist, a Physiotherapist, or a Nurse, there is no doubt that you have sacrificed some portion of your life and brain cells to hold the privilege of becoming a gatekeeper of life and death. Going through university, you are never really taught about how the so-called registration process occurs and what happens to you once you graduate. Do you just automatically become part of this secret noble club where maybe you hold a membership ID card that you can flash, declaring your stature? What you get in your dreams and what you get in reality is painfully different, and as always, ignorance and the unknown is what breeds fear, and poor decision making. In this short editorial piece, I would like to share with you all some thoughts and facts about what it means to be regulated as a healthcare professional in Australia and where there may be some gaps that need some serious reconstruction and reform.

There are currently (approx) 700,000 healthcare professionals registered in Australia holding various titles. They are all ‘registered’ under AHPRA, short for the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. This organization is not a government organization. It is not a delegated, statutory power of the Health Minister as such. It is not a company. It is not a teaching or accreditation body and or a college. It is simply an agency that, as one of its functions, helps the various Health Practitioner Boards investigate potential risk to the public. In other words, 700,000 healthcare professionals pay a fee to this agency to make sure complaints by the public are looked into, in order to keep patients safe.

The Registration process also allows practitioners to hold a prescriber number and a provider number. Without registration as a medical practitioner (or in some other health profession that would permit it) a person is not permitted to prescribe medications or claim from Medicare for medical services.

It is all about accountability and protection for the public against “bad” practitioners.

When did all this happen and who oversees what AHPRA does?

In 2008, the Council of Australian Government (COAG) decided to establish a single National Registration and Accreditation Scheme (National Scheme) for registered health practitioners. The COAG Health Council has ultimate oversight of the National Scheme. AHPRA is simply an agency that supports the National Boards (i.e. Medical Board of Australia, Dental Board of Australia, Pharmacy Board of Australia) to implement the National Scheme.

Why so serious?

That all makes sense, right? So why do so many practitioners fear and stress over the dreaded AHPRA complaint? Being accountable when holding such a title as a “Doctor” or a “Nurse” surely comes with a multitude of responsibilities and therefore, as healthcare professionals we are bred to be accountable and transparent with our work. Then why the fear? Investigation of complaints should be welcomed!

The truth is far from this. Regardless of the nature of the mistake, omission, or even criminal conduct, in a democratic society, one would think that the interrogation process is prevalent and necessary on the proviso that is it conducted fairly following the principle of due process/natural justice. However, case after case have come to light illustrating that this is not so for many who are subjected to this onerous process. It is often characterized as a never-ending investigation, onerous, with potential for long-standing conditions on your registration or slow, painful further tribunal/legal proceedings.

A classic example of a potential breach in natural justice is the fact that when a medical practitioner is referred to AHPRA, they have a panel of medical practitioners who are employed and paid by the agency to review and provide advice to other AHPRA staff who, in turn, make recommendations to the relevant board. The practitioner under scrutiny may never know that this has occurred, who the medical practitioner who reviewed their case was, what the person’s qualifications were, or whether there’s some reason why that person may not have brought a fair and impartial mind to the case. The Board may not even know this. This is one example of a flawed system that needs urgent attention from the finest minds of both the healthcare industry and the legal industry.

Knowing all this, and hearing all the nasty stories of how AHPRA or other regulatory bodies have allegedly destroyed practitioner’s lives, is fear and quasi-legal arguments and or fierce unorganized revolt the answer? Here are 5 reasons I think it should not be a fear and hate-driven process:

What’s the catch?

Although this is a NATIONAL scheme, applicable to all practitioners regardless of which state they are in, the actual NATIONAL LAW itself is a state and territory-based legislation and it is not a Commonwealth law.

Therefore, arguments regarding section 51 of the Constitution will not succeed – AHPRA/Boards are not created under Commonwealth law!

Others have thought of challenges based on section 75(iv) but recent case law and analysis of this may have made this difficult too (see below for example case law).

What to do now?

Things are changing and things will continue to change. If you are interested, read cases such as:

Craig v The Medical Board of South Australia [2001]SASC 169 this is not a recent case but it is regularly cited and gives details around what the Board should/shouldn’t do when regulating a profession.

DYB v Medical Board of Australia [2019]

If you are committed to change and would like to see this happen, there are two things you can do as a healthcare professional. One, study law and become a Lawyer. Two, support those who have already done this through fundraising and peer support groups.

Once we know what the problems are we will be able to find a solution. Surely it can’t be harder then restarting a heart that has stopped beating. Together we can create change for a fair and better tomorrow.

We are collecting data regarding need for reform. Please answer a short survey if you are a healthcare professional: Survey Monkey

Disclaimer: this article is written as an editorial /opinion and it is not a legal advice. I am not a lawyer.

The COVID-19 pandemic that has swept across the globe has caused suffering to employers, employees and the global economy. The Australian Government responded to the economic crisis with the JobKeeper payment to keep as many people in their jobs as possible. The JobKeeper payment is a $130 billion package that an eligible employer can access to keep the jobs of their eligible employees.

The JobKeeper payment was intimated in early March and was officially announced on 31 March 2020. The measures passed through parliament via the Coronavirus Economic Response Package Omnibus (Measures No. 2) Act 2020 (Cth) which will make Part 6-4C of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) (‘Act’). Since then, employers have had the ability to apply for the JobKeeper Payment that commenced on 1 May 2020, subject to the Coronavirus Economic Response Package (Payments and Benefits) Rules 2020 (Cth) (‘JobKeeper Rules’). Employers can continue to apply for the JobKeeper payment until it ends in September 2020.

At Susan Moriarty & Associates we have seen cases where employers have made workers redundant and/or dismissed them due to the economic consequences of COVID-19 without consideration/with ignorance to the JobKeeper allowance.

This article will answer the following questions:

Note: These answers are crafted in a way to give you short responses that does not delve into the detail regarding the elements that must be satisfied such as the wage condition or how the Commonwealth government calculates whether an employer is eligible for the JobKeeper allowance. Should you wish to obtain that information regarding your particular circumstances, we would be happy to help you.

1. Can I ask whether my employer has applied for JobKeeper?

You can ask your employer whether they have applied for the JobKeeper allowance. If you are an eligible employee, you can inform the employer pursuant to the Part 6-4C of the Act that you intend to participate in the scheme and want to know whether they are applying for the JobKeeper subsidy.

An ‘eligible employee’ is one that:

Section 789GB of the Act makes it clear that the purpose of the JobKeeper allowance is to keep employees employed during the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, your employer should tell you about it particularly if they are applying for the subsidy as it is a requirement they must meet. If they are not applying for JobKeeper, then they should tell you, especially if you work multiple jobs because you would need to establish which employer to get it from (as it is illegal to double-dip).

An important note is that an employer who has not applied for the JobKeeper subsidy does not have the protections given in the JobKeeper Rules and in the Act, such as being able to stand down employees with less legal risk and being able to change an employee’s responsibilities or their place of work. It is therefore beneficial for businesses to apply for the JobKeeper subsidy, and one would wonder why a business that may be suffering in the COVID-19 economic crisis would not be seeking the JobKeeper help if they are eligible.

2. If your Employer has applied for JobKeeper, do they have to tell you?

Yes. According to rule 6(4) of the JobKeeper Rules, the employer must notify an individual within seven (7) days of giving the Commissioner the employee’s details when they apply for the JobKeeper subsidy.

3. If my Employer is looking at COVID-19 related redundancies, can I raise the issue of the JobKeeper allowance?

If you are being made redundant, your employer must follow the law including discussing the redundancy with you. Section 389 of the Act states that a genuine redundancy is when:

During the consultation with your employer, you will be able to raise the JobKeeper allowance because it has been created to assist employees to keep their job. The employer will let you know if they are eligible for the payment or not, and consequently whether they will apply for it or have applied for it. If the employer has applied for the JobKeeper subsidy, they have to apply for all their employees and cannot choose who gets it and who does not.

It must be noted that there is no obligation on the employer to apply for the JobKeeper payment if they do not want to. Not applying for JobKeeper simply means the business can weather the COVID-19 economic crisis without government intervention.

If your employer is not applying for JobKeeper, section 389(2) of the Act makes it clear that the employer must consider whether it is reasonable to redeploy you to another role in the business or an associated business. If the employer fails to do so, they will be breaching the law. It would be worth in consultation to discuss this option because the availability of the JobKeeper subsidy would be taken into consideration if the employee is dismissed and the Fair Work Commission looks at whether the dismissal was harsh, unjust or unreasonable in section 389 of the Act. Make clear what you want and explore all the options, and make sure to document these discussions in writing.

4. If I am on the JobKeeper allowance, what rights do I have?

The JobKeeper payments do not change the protections you have against unfair dismissal as well as any adverse action claim about your workplace rights. The proposed section 789GY of the Act also gives further workplace rights that are protected, including:

The employer can request an employee to make an agreement regarding:

It is important to note that your contractual hours remain in effect until there is an agreement to alter it. The employer cannot take unilateral steps at changing your hours or days of work without an agreement with you. This has been a common tactic we have witnessed during this pandemic.

Whilst there are many protections and any substantive changes must be made by agreement between you and your employer, the employer does have the following powers if they are under the JobKeeper scheme:

In essence these powers give the employer the ability to give you a stand down order where necessary, however you still must be paid appropriately. The power to change duties allows the employer to provide alternative duties to the employee regardless of the contract, in an attempt to prevent standing you down. The third power allows the employer to change your place of work.

Overall if you are on the JobKeeper allowance, your workplace rights are enshrined in the JobKeeper Rules and the Act, which should prevent any unconscionable conduct by the employer. If you are being forced to accept new hours or your hours are being reduced without consent, we suggest that you talk to us about it.

5. What can I do if my employer has made me redundant/dismissed me due to COVID-19 and they do not do anything about JobKeeper?

If you have been made redundant or dismissed due to COVID-19 and JobKeeper did not make part of the consultations with you about the redundancy, then you may be able to make an unfair dismissal application or an adverse action claim against the employer. Whether you have a potential case must be analysed on a case by case basis, and that is why getting legal advice is important.

Please note that there is a 21 day timeframe in which you must make an application in the Fair Work Commission. There are some exceptions to this timeframe, however if possible, seek advice within that timeframe.

We can help you

During the current COVID-19 economic crisis, keeping your job is more important than ever and we are happy to help you and the community get through this. We are experts in employment law and have a firm grasp of the JobKeeper legislation and the current economic and legal landscape, and will be able to give you an understanding of where you can go, what you can do, and whether you have a potential case.

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer should your require advice.

Despite being in force for less than a month, the JobKeeper scheme has already attracted opportunist employers who are asking their employees for a ‘cut’ of their fortnightly payment.

According to the ABC News, reports have already been made by nervous employees that their bosses are trying to “skin the payment” from them.

Employees are being reminded the JobKeeper payment is an entitlement for their immediate benefit – not their employer, nor the business.

Importantly, employers do not have any claim over the payment and are required by the Fair Work Act to pass on the amount in full to staff. The penalties for misuse or theft can include fines and jail time.

Calls are being made for the government to create a hotline to both deter employers from being deceitful, and provide support to anxious, uncertain staff.

Read more from the ABC News here: Employers rorting JobKeeper payment will feel full force of the ATO, warns government

To understand the JobKeeper scheme and your rights as an employee read our previous blog: JobKeeper: How you are doing your employer a favour by applying for the payment

For further JobKeeper information and advice see the Fair Work Ombudsman here: https://www.fairwork.gov.au/

This article is legal information and should not be seen as legal advice. Please consult with a lawyer before you rely on this information.